If places are made of layers – dust, mud, brick, legend, name, text – what happens when one layer gets removed? A genocidal campaign on text, on history, architecture, an attempt to erase a place and to forget its former inhabitants, what Rory Finnin (2007) calls “discursive cleansing.” There is power in naming and there is power in making. Can remembering be as powerful? How do we learn “home”?

The situation of the Crimean Tatars can be summarized as: a struggle to remember, and a willfulness to persevere. An attempt to excavate a history that was brutally excoriated, a campaign to restore a lost layer, the vestiges of eras, onto a place that has continued to evolve, be written and re-written, over decades. And the denial by many that this layer, the memory of an older place, deserves to be restored.

Histories written in different alphabets are different histories. Yesterday, Milara-odzha told me that Simferopol was named Kermençik until the 13th century, Aqmescit (or Aq Mechet, “white mosque”) until 1784, when it was conquered under Catherine the Great and renamed Simferopol (from the Greek, “city of utility”). In Crimean Tatar, it would have been written this way, in Latin script, between 1928 and 1939. In 1939, the alphabet changed again along with the occupying Soviet power. Modifications were made to preserve sounds that had already been carried across different alphabetic conceptualizations of sound. In the end, two vowels didn’t make it into the Cyrillic version of Crimean Tatar, and conventions of pronunciation changed as a result. The sound of our language changed, she said.

One of the attempts by the Soviet regime to depict the deportation of the Crimean Tatars as a humanitarian relocation was to claim that Tatars would feel more at home in Central Asia, where they were linguistically and ethnically closer to the native population. Part of this is true: Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Turkmen, and Kyrgyz speak Turkic-Altaic language. They had a religion, Islam, in common. Crimean Tatars tend to have features similar to many Central Asian ethnic groups.

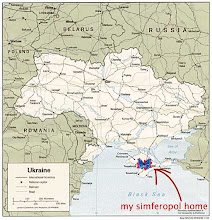

Yet despite their peaceful ability to make lives, pursue higher education, have families and community in Central Asia, most Crimean Tatars chose to return to Crimea when the path for return finally opened. These were the children, and in many cases, the grandchildren or great-grandchildren, of those deported. Yesterday, I asked a musicologist professor where life was better. His answer seemed more scientific than sentimental: “Materially, life was better in Uzbekistan. In Crimea, life is better for the soul.” His family sold their Tashkent apartment for nothing, came to Simferopol and began to build a house from scratch on the outskirts of the city. They have heat, electricity, and water now, but their house is still not finished. It was a powerful idea that made them persevere.

One of my answers to “Why Crimean Tatars? It’s so specific” is because the example of the deportation and return of the Crimean Tatars is an extraordinary example of what home means and how powerful memory can be. We theorize deterritorialization, we hear about globalization daily, I feel it most palpably now as I sit in my room in Simferopol and write something to post on the internet. Individuals break with home and feel happier that way, some create multiple homes or believe that human relationships are home. But when a collective home is rooted in place and the site becomes contested, conflicts flare up on every scale: epic disputes (

Israel-Palestine), neighborhoods campaigns (

Atlantic Yards), and contemporary genocides (

Darfur), with which we’re all familiar.

It’s trite, maybe, but Dorothy may have awoken to a startling truism. Home is potent. There’s no place like it. And while home may be unique to each individual, the case of the Crimean Tatars shows that a collective memory of home can mobilize a quarter of a million people to move thousands of miles to a place they had never actually been, but still called home.

How does a collective memory of home get transmitted? One way is through songs. Yesterday, singing about the Black Sea coast and the romance of the Crimean moon in Tatar with two little girls and their proud Tatar mother (in landlocked Simferopol), I remembered how one learns such things.

When my little brother and I were wee Ukrainian-American tots, we were taught a song that, loosely paraphrased, goes “When we grow up big and strong, brave warriors, we’ll restore our native Ukraine to its rightful hands.” (These were still Cold War years, remember.) We learned a lot of other songs, too, about Halya, Ivanko, the idyllic Carpathian mountains, and how delicious varenyky with cheese are to eat.

My family came to Ukraine for the first time, as it happened, on the day that Ukraine declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. The trip was emotional, but I was too young to really understand why. I didn’t feel like I was home (in fact everything seemed very drab and grey and alien) but I sobbed when we left. I used to cry every time I left Ukraine for years after. Though I never felt at home here, and arrivals were often jarring, it always felt like a wrenching away when I left. It felt elemental, historical, a wrenching away from a deep connection to place - possibly, a symptom of the inheritance of home.

---

On a totally unrelated and much lighter subject: The Debutante Hour EP is now available for purchase online, Weeee! It’s economical and special. You can buy your very own copy

here.I spent the entire day pretty much hanging out at Milara-odzha’s house with her daughters, a visiting artist, and her husband. It was really fun and I learned a lot. Heart and Soul is going to be a big hit when the girl’s perform it on International Women’s Day (March 8th).

And, to satisfy those of you who have been asking, here's a photo of me with my younger host brother Pasha. (That's still what I look like, thanks for reading my blog.) Pasha and I have the most amazing avant-garde conversations in English. Here's a loose transcript of the conversation we had right before this photo was taken:

And, to satisfy those of you who have been asking, here's a photo of me with my younger host brother Pasha. (That's still what I look like, thanks for reading my blog.) Pasha and I have the most amazing avant-garde conversations in English. Here's a loose transcript of the conversation we had right before this photo was taken:

So, I convinced Milara that we should go for a walk. That was fun. Women in this part of the world tend to take other women under the arm, and I quite like walking around like that. We promenaded by a statue and she told me the legend of

So, I convinced Milara that we should go for a walk. That was fun. Women in this part of the world tend to take other women under the arm, and I quite like walking around like that. We promenaded by a statue and she told me the legend of